Let-bindings and simple stack allocations

Based on these notes by Ben Lerner. Shortened/simplified a bit, changed the concrete syntax, and cut in two separate notes.

1 Growing the language: adding let

As above, every time we enhance our source language, we need to consider several things:

Its impact on the concrete syntax of the language

Examples using the new enhancements, so we build intuition of them

Its impact on the abstract syntax and semantics of the language

Any new or changed transformations needed to process the new forms

Executable tests to confirm the enhancement works as intended

1.1 The new syntax, both concrete and abstract

Let’s grow the language above further, by adding the concepts of identifiers and let-bindings:

and its corresponding abstract syntax

type expr = ...

| Id of string

| Let of string * expr * expr1.2 Examples and semantics

Recall the semantics of let.

In the interpreter, we can use an environment to track the meaning of bound identifiers.

The environment would have type type env = (string * int) list, assuming

we are going to adopt eager evaluation.

Do Now!

Suppose we added an expression

Print of exprthat both prints its argument to the console, and evaluates to the same value as its argument. Construct a program whose behavior differs depending on whether we adopt eager or lazy evaluation.

Inner let-bindings shadow outer ones: (let (x 1) (let (x 2) x)) evaluates to 2.

The program (let (x 5) (add1 y)) is meaningless, because y is free.

Also, recall the let introduces the identifier only in its body, not in the bound expression.

1We’ll see somewhat later how to implement let rec,

where x is available in both subexpressions.

Now that we’ve reminded ourselves of what our programs are supposed to mean, let’s try to compile them instead of interpreting them. For now, let’s assume that scoping errors cannot happen; we’ll need to revisit this faulty assumption and ensure it later.

2 The stack

Immediately, we can see two key challenges in compiling this code: in the little fragment of assembly that we currently know, we have no notion of “identifier names”, and we certainly have no notion of “environments”. Worse, we can see that a single register can’t possibly be enough, since we may need to keep track of several names simultaneously.2To be fair, this language is simple enough that we actually don’t really need to; we could optimize it easily such that it never needs more than one. But as such optimizations won’t always work for us, we need to handle this case more generally. So how can we make progress?

One key insight is to broaden what we think of when considering names. In our interpreter, a name was used to look up what value we meant. But realistically, any unique identifier will suffice, and all our values will ultimately need to exist somewhere in memory at runtime.

Therefore we can replace our notion of a name is a string with a

name is a memory address. This leads to our second key insight: during

compilation, we can maintain an environment of type env = (string * address) list

(for some still-to-be-determined type address). We can extend

this environment with new addresses for new identifiers, each time we compile a

let-binding, and we can look up the relevant address every time we compile an

identifier. Once we’ve done so, we don’t need this environment at

runtime —

This eliminates both of our representation problems (of how to encode string names and the whole environment), but raises a new question: how do we assign addresses to identifiers in a sufficient way?

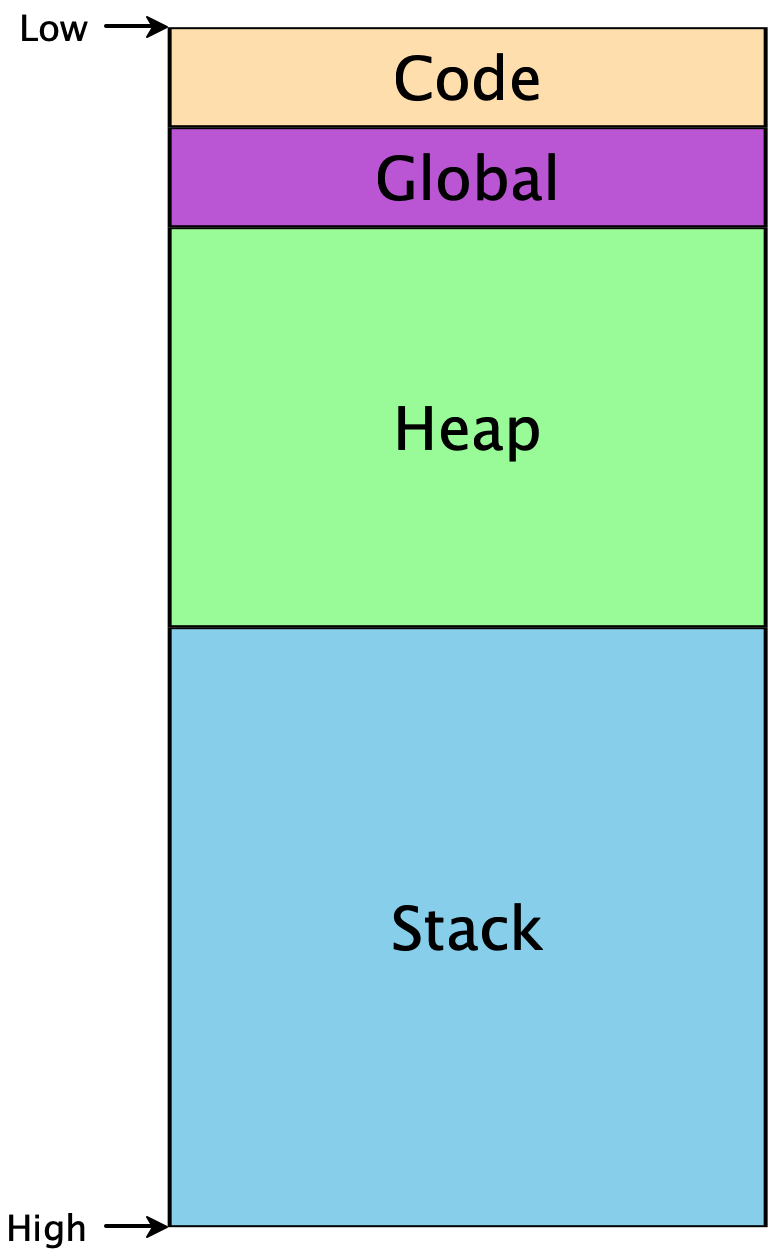

To make any further progress, we need to know a little bit about how memory is used in programs. Memory is conceptually just a giant array of bytes, addressed from 0 to 264 (on 64-bit machines). There are restrictions on which addresses can be used, and conventions on how to use them appropriately. Programs don’t start at memory address 0, or at address 264, but they do have access to some contiguous region:

The Code segment includes the code for our program. The Global

segment includes any global data that should be available throughout our

program’s execution. The Heap includes memory that is dynamically

allocated as our program runs —

Because the heap and the stack segments are adjacent to each other, care must be taken to ensure they don’t actually overlap each other, or else the same region of memory would not have a unique interpretation, and our program would crash. This implies that as we start using addresses within each region, one convenient way to ensure such a separation is to choose addresses from opposite ends. Historically, the convention has been that the heap grows upwards from lower addresses, while the stack grows downward from higher addresses.3This makes allocating and using arrays particularly easy, as the ith element will simply be i words away from the starting address of the array.

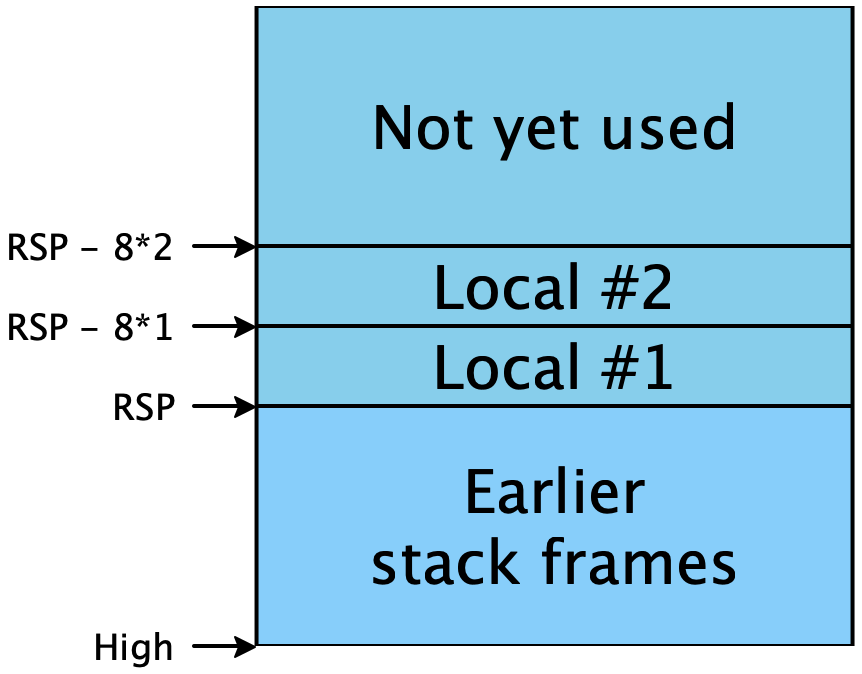

The stack itself must conform to a particular structure, so that functions can

call each other reliably. This is (part of) what’s known as the calling

convention, and we’ll add more details to this later. For now, the high-level

picture is that the stack is divided into stack frames, one per

function-in-progress, that each stack frame can be used freely by its function,

and that when the function returns, its stack frame is freed for use by future

calls. (Hence the appropriateness of the name “stack”: stack frames obey a

last-in-first-out discipline as functions call one another and return.) When a

function is called, it needs to be told where its stack frame begins. Per the

calling convention, this address is stored in the RSP register (short for

“stack pointer”)4This is a simplification. We’ll see the fuller rules

soon.. Addresses lower than RSP are free for use; addresses

greater than RSP are already used and should not be tampered

with:

3 Allocating identifiers on the stack

The description above lets us refine our compilation challenge: we have an

arbitrary number of addresses available to us on the stack, at locations

RSP - 8 * 1, RSP - 8 * 2, ... RSP - 8 * i. (The factor of 8

comes because we’re targeting 64-bit machines, and addresses are measured in

bytes.) Therefore:

Exercise

Given the description of the stack above, come up with a strategy for allocating numbers to each identifier in the program, such that identifiers that are potentially needed simultaneously are mapped to different numbers.

3.1 Attempt 1: Naive allocation

One possibility is simply to give every unique binding its own unique integer. Trivially, if we reserve enough stack space for all bindings, and every binding gets its own stack slot, then no two bindings will conflict with each other and our program will work properly.

In the following examples, the code is on the left, and the mappings of names to stack slots is on the right.

(let (x 10) (* [] *)

(add1 x)) (* [ x --> 1 ] *)

(let (x 10) (* [] *)

(let (y (add1 x)) (* [x --> 1] *)

(let (z (add1 y)) (* [y --> 2, x --> 1] *)

(add1 z)))) (* [z --> 3, y --> 2, x --> 1] *)

(let (a 10) (* [] *)

(let (c (let (b (add1 a)) (* [a --> 1] *)

(let (d (add1 b)) (* [b --> 2, a --> 1] *)

(add1 b)))) (* [d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] *)

(add1 c))) (* [c --> 4, d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] *)We can implement this strategy fairly easily: simply keep a global mutable

counter of how many variables have been seen, and a global mutable table

mapping names to counters. But as the last example shows, this is wasteful of

space: in the final line, neither b nor d are in scope, but their

stack slots are still reserved. As programs get bigger, this would be very

inefficient.

An equally important, though much subtler, problem is the difficulty of

testing this implementation. We would expect that compile_expr

should be a deterministic function, and that compiling the same program twice

in a row should produce identical output. But because of mutable state, this

is not true: the second time through, our global counter has been incremented

beyond its initial value, so all our stack slots will be offset by an unwanted

amount. We could try to resolve this by having some way to “reset”

the counter to its initial value, but now we have two new hazards: we have to

remember to reset it exactly when we mean to, and we have to remember

not to reset it at any other time (even if it would be “convenient”).

This is an example of the singleton anti-pattern: having a single global value

is almost always undesirable, because you often want at least two such values

—

3.2 Attempt 2: Stack allocation

A closer reading of the code reveals that our usage of let bindings also forms a stack discipline: as we enter the bodies of let-expressions, only the bindings of those particular let-expressions are in scope; everything else is unavailable. And since we can trace a straight-line path from any given let-body out through its parents to the outermost expression of a given program, we only need to maintain uniqueness among the variables on those paths. Here are the same examples as above, with this new strategy:

(let (x 10) (* [] *)

(add1 x)) (* [ x --> 1 ] *)

(let (x 10) (* [] *)

(let (y (add1 x)) (* [x --> 1] *)

(let (z (add1 y)) (* [y --> 2, x --> 1] *)

(add1 z)))) (* [z --> 3, y --> 2, x --> 1] *)

(let (a 10) (* [] *)

(let (c (let (b (add1 a)) (* [a --> 1] *)

(let (d (add1 b)) (* [b --> 2, a --> 1] *)

(add1 b)))) (* [d --> 3, b --> 2, a --> 1] *)

(add1 c))) (* [c --> 2, a --> 1] *)Only the last line differs, but it is typical of what this algorithm can

achieve. Let’s work through the examples above to see their intended compiled

assembly forms.6Note that we do not care at all, right now, about

inefficient assembly. There are clearly a lot of wasted instructions that move

a value out of RAX only to move it right back again. We’ll consider

cleaning these up in a later, more general-purpose compiler pass. Each

binding is colored in a unique color, and the corresponding assembly is

highlighted to match.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Additionally, this algorithm is much easier to implement than the previous one:

adding a binding to the environment simply allocates it at a slot equal to the

new size of the environment. As we descend into a let-binding, we keep the

current environment. As we descend into a let-body, we augment the environment

with the new binding. And as we exit a let-expression, we discard the

augmented environment —

4 Implementing let with Stack Allocation

4.1 Extending our transformations

We need to enhance our definition of registers and arguments:

type reg = ...

| RSP (* the stack pointer, below which we can use memory *)

type arg = ...

| RegOffset of reg * int (* RegOffset(reg, i) represents address [reg + 8*i] *)type env = (string * int) listfun lookup name env =

match env with

| [] -> failwith (sprintf "Identifier %s not found in environment" name)

| (n, i)::rest ->

if n = name then i else (lookup name rest)fun add name env : (env * int) =

let slot = 1 + (List.length env) in

((name, slot)::env, slot)Now our compilation is straightforward. We sketch just the let-binding case; we leave the others as an exercise:

let rec compile exp env =

match exp with

| Let(x, e, b) ->

let (env', slot) = add x env in

(* Compile the binding, and get the result into RAX *)

(compile e env)

(* Copy the result in RAX into the appropriate stack slot *)

@ [ IMov(RegOffset(RSP, -8 * slot), Reg(RAX)) ]

(* Compile the body, given that x is in the correct slot when it's needed *)

@ (compile b env')

| ...4.2 Testing

Exercise

Complete this compiler, and test that it works on all these and any other examples you can throw at it.

4.3 FAQ

- What happens when the stack grows beyond its limit?

Normally, the stack size should not be a problem, because it’s usually large enough to accommodate many local variables and active function calls.

In specific cases, one can usually customize the stack size when needed (e.g. using ulimit -s new_size on Linux).

But, who knows? Especially in languages without tail call optimization, deep recursion can easily hit the size limit. Recall these notes.

At the lowest level, of course, there is no magic: if one goes beyond the stack limit, one can overwrite data used by others, starting with the heap, which is the first area of memory exposed beyond the stack limit. This can lead to any kind of unpredictable behavior.

Some compilers can make sure it is not possible to go beyond the stack limit.

For instance, gcc has an option to activate stack checking.

This flag tells the compiler to insert extra instructions that check any use of the stack, and raise an exception if the space is exceeded.

In general, implementations of safe languages (Java, Python, Scheme, OCaml, etc.) perform such checks, and also raise an exception whenever the stack reaches its assigned limit.

1We’ll see somewhat later how to implement let rec,

where x is available in both subexpressions.

2To be fair, this language is simple enough that we actually don’t really need to; we could optimize it easily such that it never needs more than one. But as such optimizations won’t always work for us, we need to handle this case more generally.

3This makes allocating and using arrays particularly easy, as the ith element will simply be i words away from the starting address of the array.

4This is a simplification. We’ll see the fuller rules soon.

5A growing trend in compiler architecture is to design a language server, which basically takes the compiler and leaves it running as a service that can be repeatedly queried to recompile files on demand. This helps amortize the increasingly large startup cost of sophisticated compilers, and makes it much easier to build language support for new languages into new editors. But having “compilers as a service” implies that they must be exceedingly careful of mutable state, or else subsequent compilations might produce different, potentially incorrect, results than earlier ones!

6Note that we do not care at all, right now, about

inefficient assembly. There are clearly a lot of wasted instructions that move

a value out of RAX only to move it right back again. We’ll consider

cleaning these up in a later, more general-purpose compiler pass.